I was supposed to be going to Capel-y-ffin, just north of Llanthony, back last January to make a radio programme about Thin Places – then the lockdown struck. We decided to have another go on Tuesday. In folklore (and in some pre-Christian traditions), thin places are literal doors to the Other World. Stories of shepherds who walk into a stone circle or a cave, find themselves in the land of the fairies, dance with them all night, fall asleep, and when they wake up they find that a hundred years have passed and everyone they knew is dead …

In the Christian tradition, it’s a bit different – they are places where you are particularly aware of the presence of God and the nearness of the Other. But are they inherently like that, or are they created by the prayers of the faithful – what T. S. Eliot called places ‘where prayer has been valid’? Llanthony is a bit of both. The legend is that the medieval priory was founded by a young knight of the local de Lacy family. Out hunting, he became separated from his companions and got to a little ruined hermitage. He was told it was where St David had gone in retreat. He became a hermit there, and attracted so many followers that his hermitage developed nto a community of Augustinian canons.

So did the place speak to him, or did he realise it was holy when he found about St David? And was St David ever really there? And are thin places always quiet, remote retreats? For me, the ultimate thin place is Penrhys – which is a busy and sometimes troubled housing estate on the site of a medieval shrine to the Virgin Mary. The estate church is a centre of prayer and social activism, somewhere the Gospel is really being lived – but it isn’t everyone’s idea of a spiritual refuge.

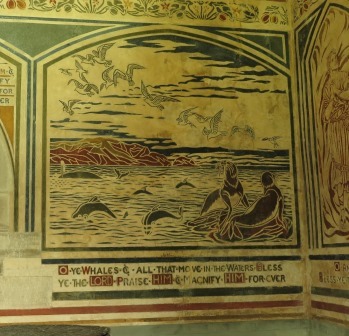

We stopped off on the way to Capel-y-Ffin at Llanthony Abbey. As well as the abbey ruins, the parish church was made out of the abbey infirmary. It has some splendid painted wall memorials – none by the famous Brute family of stonemasons but plenty to admire. Bob Silvester’s article in the current Church Monuments is a really good study of these local stonemasons My photos aren’t brilliant because I only had my phone and it was very dark, but they give you an idea.

The Trumper monument

commemorates several generations of the family. There’s a particularly good angel at the top, with the trumpet of the Last Judgement (a pun, maybe?) standing on some very fluffy clouds.

Next to this, the monument to William and Sarah Jones

has two urns at the top and a sort of bathtub with the text ‘The just shall live by faith’.

There’s an intriguing difference in the lines under their names. His reads

Time swiftly flies, and calls away

Our spirits to their home;

Our bodies mingle with the clay

And rest beneath the stone.

Resignation, and the earthly fate of the body.

Hers by contrast reads

Strong was her faith in him

who died to save

And bright her hope of joy

beyond the grave.

more of a sense of religious belief. I’ve seen the same difference between men’s and women’s inscriptions elsewhere but I’m not sure if it’s a real gendered difference.

I couldn’t get a good picture of the one above

but it commemorates an earlier William Jones with the lines ‘Remember man that die thou must, and after death return to dust’ and ‘The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.’

Next to this is a monument to Mary Davis and her husband Roger Davis, perpetual curate of the parish

with a trumpet-wielding cherub at the top and the lines ‘How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace, and bring glad tidings of good things!’ – very appropriate for a cleric.

The Lewis monument

is particularly colourful, and has something of a gendered difference in the poems. His is

Behold o mortal man

How swift thy moments fly

Thy life is but a span

Prepare thyself to die.

Hers is

Extend to me thy favour, Lord,

Thou to thy chosen dost afford.

When thoui returnst to set them free

Let thy salvation visit me.

Sorting out the Joneses was tricky, but this one came from the neighbouring parish of Craswall, across the Hatterall ridge and in the next county and diocese.

An urn sitting on a bath tub (technically they are called ‘wine coolers’) this time, with the words ‘Memento mori’. Underneath is the verse

The soul prepared made no delay,

The summons comes, the saints obey;

The flesh rests here till Jesus comes

To claim the treasures from the tombs.

Really difficult to photograph, this one, on the east side of the chancel arch

Mary and William Parry of Nantycarne, a farm tucked into the hillside just north of the abbey. Both have Bible quotes. His is from the Book of Revelation: ‘Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord. Yea, saith the spirit, that they may rest from their labours.’ Hers is really unusual, lines from chapter 7 of the Book of Job. ‘The eye of him that hath seen me shall see me no more. His eyes are upon me and I am not. As the cloud is consumed and vanisheth away, so he that goeth down to the grave shall come up no more.’

What can have led Mary (or her family) to those strangely disturbing lines? Extracts from the Book of Job feature heavily in the medieval Office of the Dead, the night prayers said after a death and before the funeral. But that would have been in Latin, and those particular verses only appear in a couple of unusual variants of the liturgy.

The other interesting thing is that the wording isn’t exactly that of the Authorised Version, which is ‘…thine eyes are upon me and I am not’. It does sound as though the wording was given from memory, suggesting it was a text known well but not quite well enough.

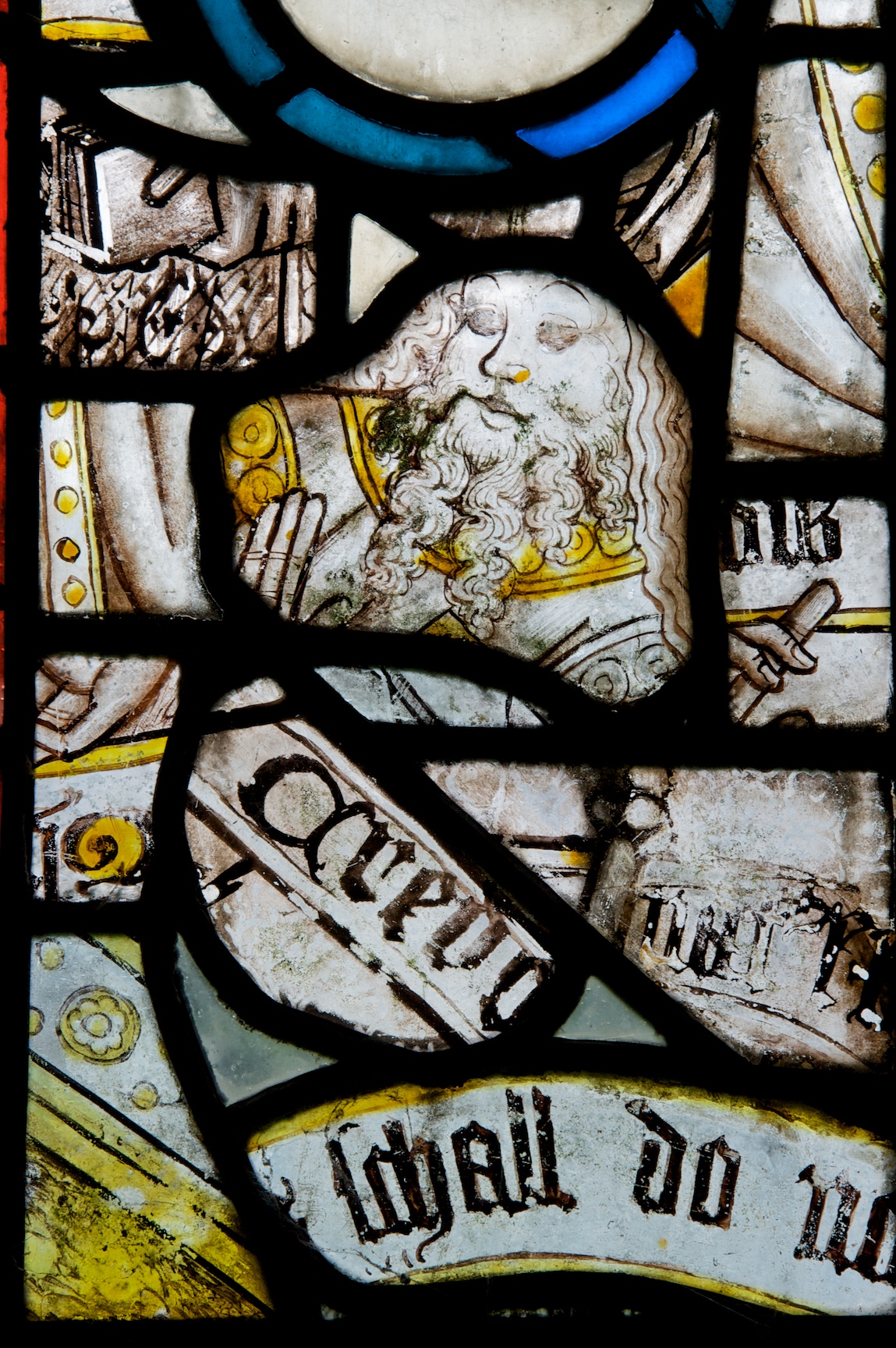

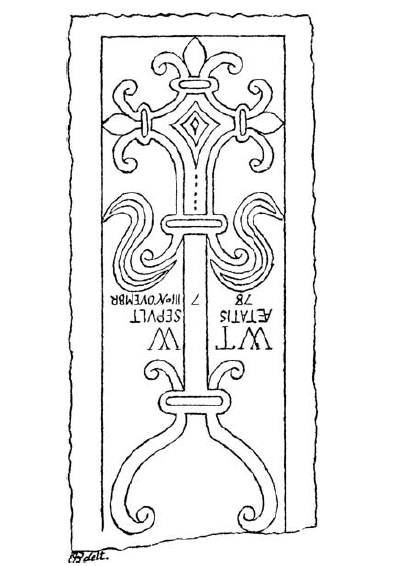

But the real excitement was this

half hidden in the south-west corner. How many times have I been to the church and failed to spot it – how many groups of students have I taken there – I’ve been there with the Stone Forum, with the Church Monuments Society –

and there it was, hiding in plain sight, a medieval cross slab, trimmed on a slight slant, repurposed at least once with a later inscription.

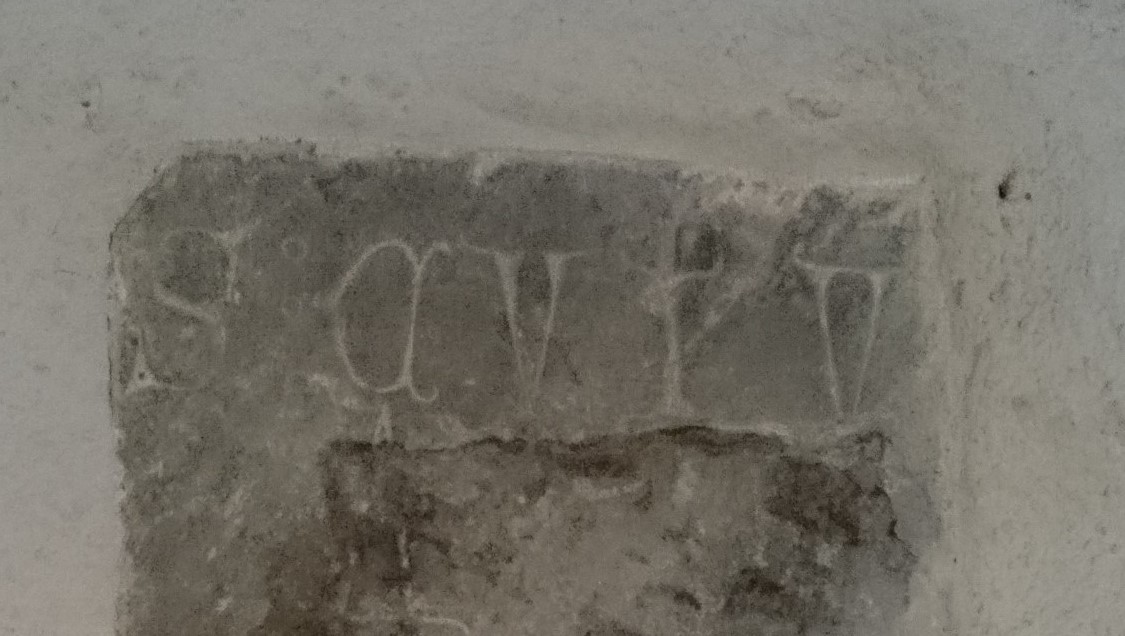

The detail of the head

suggests a late date, probably fifteenth century. The base

has a fleur-de-lys decoration rather than a stepped base which makes me think it’s 15th rather than early 16th. And the inscription –

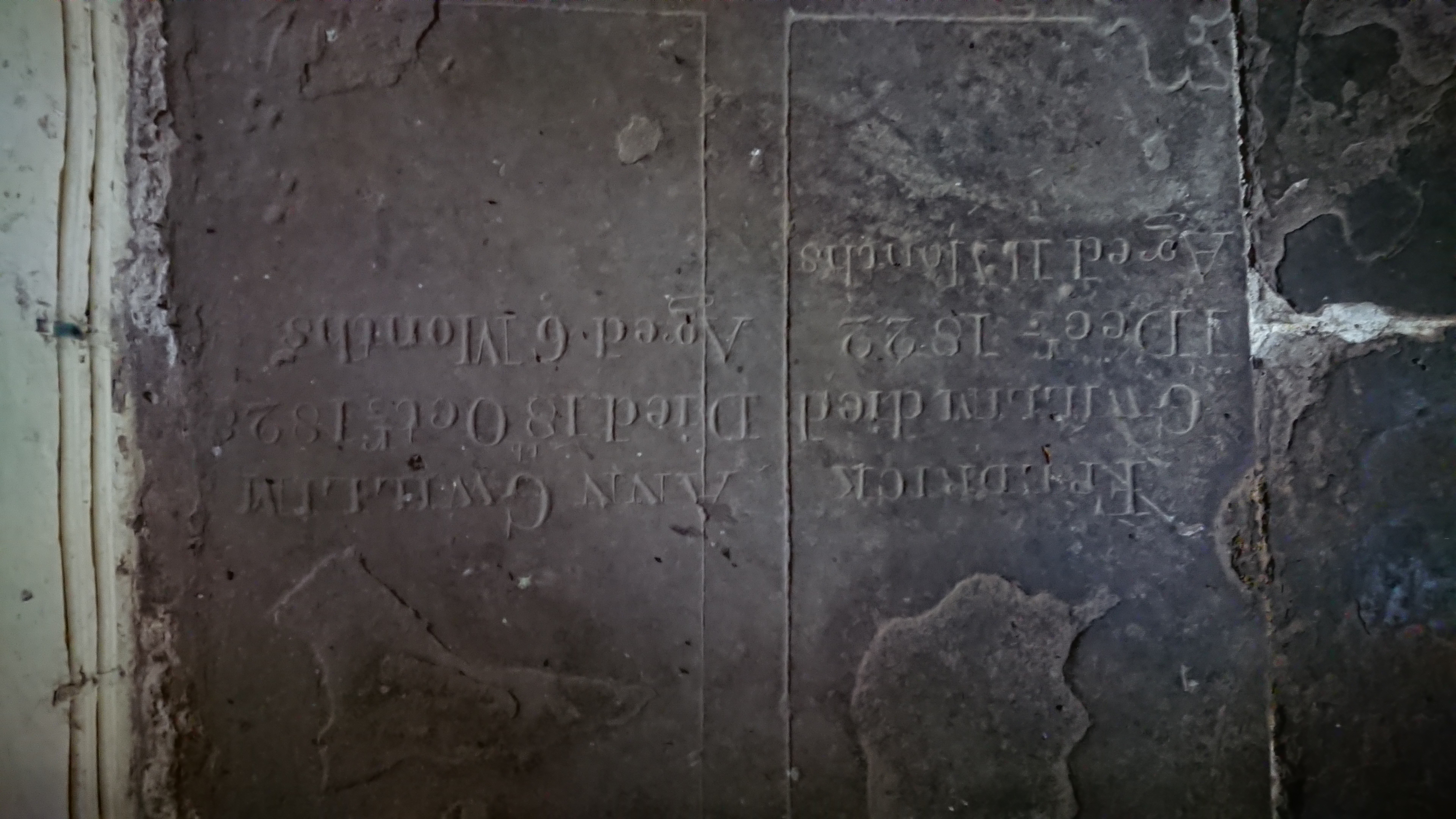

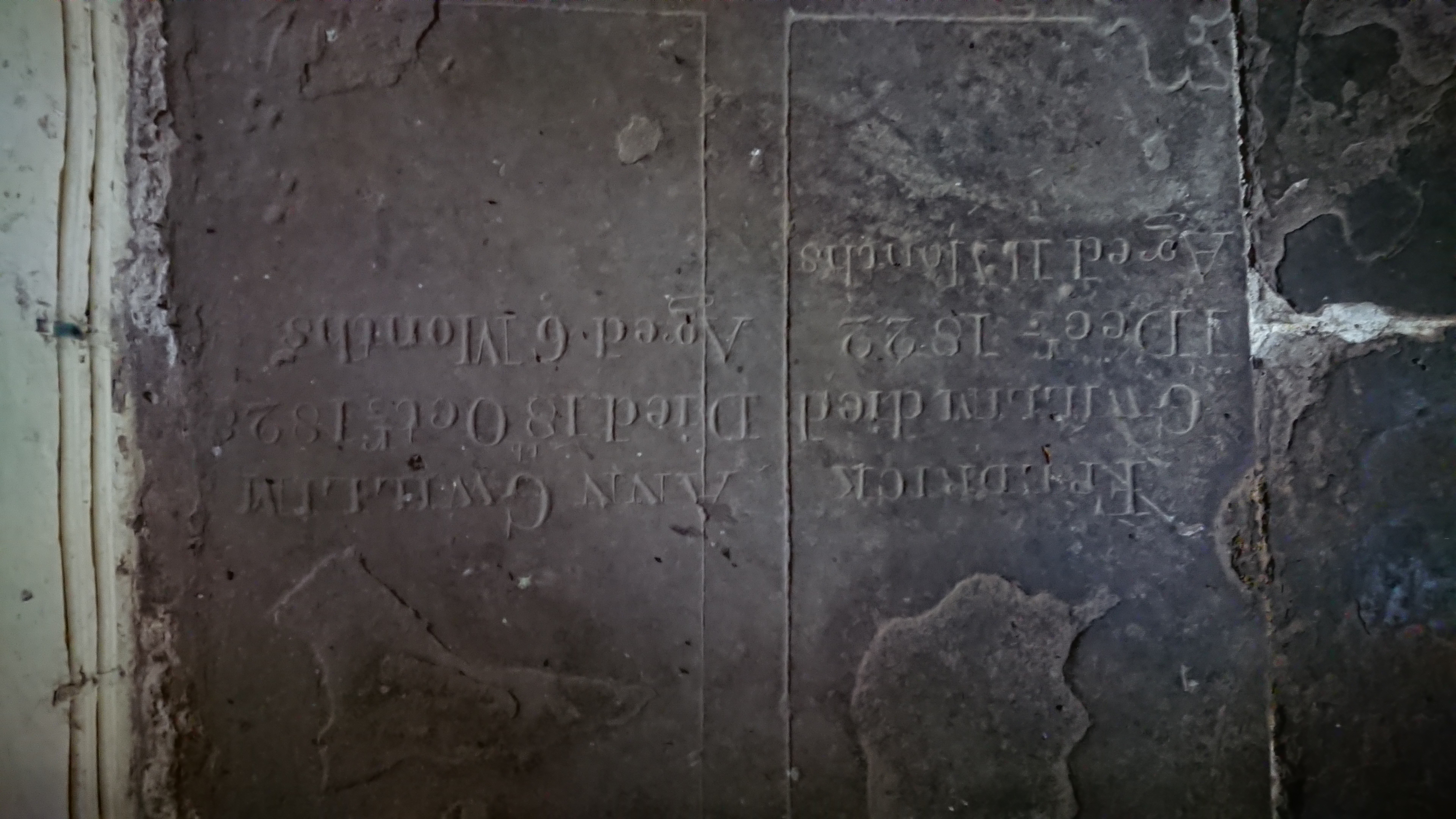

two family tragedies. Frederick Gwillim, Died 1 Decr 1822 aged 11 months, and Ann Gwillim, Died 18 October 1828 aged 6 months. How did they bear it.

Probably the stone came from the abbey – possibly the grave of a leading member of the community, possibly a lay person who had been generous to them. Who knows.

Llanthony was a bit disconcerting, being full of young army recruits, all spick and span in their new camouflage gear and 20 kilo overnight packs, off on an exercise in the mountains. The road to Capel y Ffin was nearly blocked by a landslide but Steve managed to get through. And the recording went well. They didn’t really want a lot of detail, and it was good to see the little church again.