Persevering with the rescuing of articles from the Gwent County History Association’s Newsletter: this is roughly the text of a lecture to the Friends of Llandaff Cathedral based on my article ‘The Cloister and the Hearth: Anthony Kitchin and Hugh Jones, two Reformation bishops of Llandaff’ in the Journal of Welsh Religious History vol 3, 1995. The article has notes of all the sources I have used. At the end is the original Newsletter article, the rather pathetic survey of his property at the time of his death.

Anthony Kitchin is not perhaps the most auspicious of our bishops. He served as bishop of Llandaff all through the religious turmoil of the middle of the sixteenth century, under Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth. He has been repeatedly accused by historians of greed, ignorance and ineptitude as well as total lack of principle. My lecture was therefore in some senses the speech for the defence.

The case for prosecution stands in the outline of his career. A monk from the great Benedictine abbey of Westminster, he rose to become abbot of Eynsham, near Oxford. He surrendered his abbey without protest in 1538, showing none of the courage in resistance offered by men like John Houghton of the London Charterhouse and the abbots of Glastonbury, Reading and Colchester. Having been made bishop of Llandaff in 1545, he clung to office through the reigns of Edward and Mary, again showing none of the brave resistance of Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley, or of the Edwardian bishop of St David’s, Robert Ferrar. He was one of only two Marian bishops to accept the Elizabethan settlement (the other, frequently forgotten, was John Salisbury of Sodor and Man). On the face of it, then, his defence is a virtually impossible task.

We cannot even claim that Kitchin was the ‘reclusive child of the cloister’ described by Lawrence Thomas in The Reformation in the Old Diocese of Llandaff – that he could not cope with the challenges of the world outside his monastery. This is a fundamental misinterpretation of the religious life in the late middle ages. As abbot of Eynsham, Kitchin managed a budget several times that of his future diocese. Indeed, his pension after the Dissolution was only a little less than the total income of the diocese of Llandaff. (He surrendered his pension when he took on the diocese – which I think incidentally puts paid to the charge of greed.)

Nor had he a naive young man when he embarked on the religious life. He was aged about 34 when, in 1511, he entered the abbey of Westminster. He celebrated his first mass in 1517, at the age of 40. By this time, his intellectual abilities had already been noticed and he had begun his studies at Gloucester College, the Benedictine college in Oxford, where he proceeded B.D. in 1525. Though a competent theologian (the charge of ignorance will not stand, either), he was always an administrator rather than an academic. The year after his graduation, he was made prior of Gloucester College, a post he held until he was elected abbot of Eynsham in 1532. He did not however take his doctorate until 1538, shortly before he surrendered his abbey to the Crown. He may have been planning for a career change: or, like many of my best students, he may have been one of those whose serious academic work was done at the end rather than the begining of his working life.

The headship of Gloucester College was a challenging post, even for a mature student like Kitchin. Then as now, university life offered unaccustomed freedom to young students, even if they were monks. They had to balance obedience to their vows and to the rule of their order, and the regular performance of the liturgy, with intellectual freedom, the demands of study and the social opportunities of university life. In addition, the 1520s presented particular challenges. Reformed theology was beginning to filter into English universities, and was being met with increasing hostility by the establishment. The prior of students needed considerable pastoral skill to guide his charges through these temptations. He also needed negotiating ability. Gloucester College was not so much a unfied institution as a loose federation, a hall with individual ‘staircases’ owned or leased by particular monasteries. Groups of students from the greater abbeys had their own superiors, but Kitchin had to exercise supervision over all of them. He was also required to impose some sort of authority over the Benedictine monks who for various reasons were studying at other colleges. This was presumably where he developed the ability to negotiate, to compromise and to give in on some issues in order to preserve his priorities, the ability which has earned him so much criticism.

In later life, Kitchin was undoubtedly conservative in his religious sympathies. At Oxford, however, he responded to the intellectual excitement of the new theology and was even involved in the clandestine trade in Protestant books. As abbot of Eynsham, he was active in the crucial Reformation parliament of 1529-36. However, the reformers’ attack on his chosen way of life may have disquieted him. There were rumours early in 1537 that he and the abbot of Osney had been involved in support for the Pilgrimage of Grace. They were accused of unlawful assembly and disrespect to the King’s commission and of associating with other supporters of the Pilgrimage. The whole story is confusing and obscure and depends on the testimony of an informer, John Parkins, who may have been motivated by personal grudges.

Kitchin surrendered his abbey with apparent willingness in December of the following year. He has been accused of cowardice in this as in other things, but it is at least arguable that he proceeded from conviction. He had evidently made his peace with the Crown: he received a generous pension and was made a royal chaplain in ordinary. This was little more than an honorary post. He was in his sixties, and could have looked forward to a blameless retirement. Instead, a new career was ahead of him.

Like the other Welsh dioceses, Llandaff had been inadequately served by its bishops for generations. They were pitifully poor in comparison with the English dioceses, and had customarily been regarded as little extras for royal servants and abbots of the greater English religious houses. It was hardly to be expected that these outsiders would spend much time in Wales, though some bishops of Llandaff are known to have visited the episcopal palace at Mathern – as near to England, geographically and culturally, as one could get while still technically in a Welsh diocese. The most extreme example is perhaps George of Athequa, bishop of Llandaff at the time of Henry’s break with Rome. He was Catherine of Aragon’s confessor and one of her most loyal servants: but he spoke neither English nor Welsh, and he may only have visited his diocese once, while attempting to flee the realm after Catherine’s death.

Robert Holgate, who replaced Athequa in 1538, was the former master of the Gilbertine order. A distinguished theologian and capable administrator and a dedicated reformer, he was also yet another absentee with heavy governmental responsibilities elsewhere. In Holgate’s case, this meant the presidency of the Council in the North, which kept him away from his diocese for most of his time in office. A conscientious man, he attempted to keep in touch with his Welsh diocese through his commissary, and appointed as suffragan John Bird, bishop of Penrith: but when Bird was sent on an embassy to Germany in 1539 and appointed to the diocese of Bangor on his return, Llandaff was left without a resident bishop again until Kitchen’s appointment.

Holgate was eventually promoted to the archbishopric of York in 1545, and it is hard to see why Kitchin was chosen to replace him. He was however appointed at the height of the conservative, Catholic revival at the end of Henry VIII’s reign. Holgate’s reforming ideas had had little or no impact on his Welsh diocese, and may even have been counter-productive. After his earlier interest in reform, Kitchin had become just the sort of moderate conservative to appeal to the ageing king. If his conciliatory abilities had been recognised, he may even have been appointed as a troubleshooter in an attempt to win over a stubborn and difficult diocese.

Kitchin’s career as bishop has been fully documented, notably by Lawrence Thomas, Glanmor Williams and J. Gwynfor Jones. It is however possible to suggest an interpretation of his policies radically different from the traditional one. The strongest criticisms have often been directed at his mismanagement of the diocesan estates. We can easily dismiss his early seventeenth-century successor Francis Godwin’s claim that Kitchin found the diocese one of the wealthiest in the land and left it one of the poorest. This seems at first sight to owe more to Godwin’s second career as a science fiction writer than to his main occupation as a church historian. It is best interpreted as an argument in support of of his plea to be allowed to retain the sub-deanery of Exeter as well as several parishes on his appointment to Llandaff. In this context, it is worth remembering that the ‘greedy’ Kitchin held no preferments in commendam and no Crown office. This makes him virtually unique among bishops of Llandaff before the last century. It is also worth remembering that he sacrificed his pension and retirement for Llandaff, and that he died in considerable poverty. Godwin was himself accused of having resorted to bribes – the dreadful sin of simony – to secure both his appointment at Llandaff (and why did he want it so much, if it was worthless?) and his eventual removal to Hereford. Most of his time at Llandaff was spent working on his ecclesiastical history and ignoring the growing problem of recusancy. Not a very reliable witness, you might think …

The mid-sixteenth century was a period of sustained pressure on the estates of the secular church. Henry VIII began the process by a series of unfavourable ‘exchanges’ which deprived the wealthier dioceses of some of their lands and left them increasingly dependent on the exploitation of parochial income. During Edward’s reign, the increasingly straitened condition of government finances led both Somerset and Northumberland to demand the surrender of diocesan estates on the grounds that they were inappropriate to a reformed episcopacy. Meanwhile, the aristocracy and higher gentry, again led by Somerset and Northumberland, were demanding grants and beneficial leases of church property for their personal benefit.

The diocese of Llandaff was abysmally poor by English standards and had little land to lose, though this did of course make it more important to retain what there was. In fact, Kitchin did this with some success. Virtually no land was alienated outright during his episcopate. Generations of largely absentee bishops had leased out the diocesan estates at rents which had become ossified by tradition. After a century during which land values in Wales collapsed in the wake of famine, plague and civil war, the sixteenth century was a period of inflation and rising rents. The worst that Kitchin did was to fail to recognise this, and it was a failing which was shared by most of his contemporaries. Even the episcopal manor of Llandaff, leased in perpetuity to the Matthews family of Llandaff in 1553, was let subject to the traditional rent. However, most of Kitchin’s leases were for fixed terms and, in effect, by leasing out his lands for long terms and at the customary rents, he made them far less attractive to the Crown and the lay aristocracy. If this was deliberate policy on Kitchin’s part, it was extremely cunning; if it was accidental, he was fortunate, though it was not a policy which would recommend him to his immediate successors.

The only major permanent loss which the diocese suffered in the sixteenth century was its London residence, Llandaff Palace in the Strand. This Kitchin was compelled to surrender to the duke of Somerset, who demolished it (along with the houses of Worcester and Carlisle) to build the original Somerset House. The London palaces were however a diminishing asset, often in poor repair and hideously expensive to maintain. Norwich Palace was described as a ‘pigsty’ in 1528. The same could be said of the episcopal palace at Llandaff, virtually in ruins as a result of the complete neglect of a series of absentee bishops. It would have taken far more than the diocese was worth to restore these two houses.

The palace at Mathern had been kept in some sort of repair as a convenient base for occasional episcopal visits, and it was here that Kitchin lived. He has been accused of leasing even this central part of his estate, but it was certainly at Mathern that he died, and his successor lived there. The lease was to his neighbour William Lewis, son of Henry Lewis of St Pierre. The traditional view of the local gentry as enemies of the church in the sixteenth century is being re-assessed, and many of the activities which have traditionally been regarded as exploitation are now being interpreted as attempts to support the church.[i] Kitchin remained close to the Lewis family, and William Lewis was executor of his will. It may be that what we have here is a collusive lease, a device to tie up the manor and lands by handing them over to a trustworthy friend to keep them safe from expropriation.

Perhaps a more fundamental criticism of Kitchin as a churchman is the apparent ease with which he acquiesced in a series of radical religious changes. He compares badly with the Marian martyrs, and with those conservative bishops who suffered various degrees of imprisonment under Edward and Elizabeth. He was not incapable of standing up for his opinions, but he was, perhaps understandably, reluctant to push his opposition to the point at which he could be removed from office. It seems to me that we should be careful in our assumptions about what we expect from people of principle. In an age of democracy and relatively free speech, we need to remember the potentially appalling consequences of arguing with the Tudor monarchs. We also need to consider whether a head-on challenge was always the most productive course of action. Men like Cranmer had no choice. For others, there were the alternatives of escape to the Continent (like William Barlow, former bishop of St David’s) or a quiet life in a country parish (like Matthew Parker, future archbishop of Canterbury). I would like to suggest that it is equally ethical (and possibly equally brave) to make a decision to remain in your post and to do what you can from a position of power to mitigate the impact of policies which you deplore.

For example, in spite of his early involvement with reform, Kitchin always opposed the idea of clerical marriage, and stood out against it in the 1549 Parliament. He also opposed the Government line on the theology of the Eucharist. In 1554, again, he took his own line when, on the reconciliation of the kingdom with Rome, he was the only bishop not to seek absolution from the sin of schism. In his own mind, he does not seem to have considered himself a schismatic, and he could well have argued that he had also protected his diocese from sin.

In 1559, along with the other Marian bishops, Kitchin voted in the Lords against the restoration of the royal supremacy and the Act of Uniformity. The Elizabethan settlement is yet another area of sixteenth-century history which has been the subject of recent re-appraisal. The traditional view was that Elizabeth was pushed towards a more radical settlement than she wanted by Protestant opinion in the House of Commons. Recent studies have argued that Elizabeth and her advisers got more or less the settlement that they wanted, but that they were held up for some time by the determined opposition of the bishops in the Lords. It was not until some of these intransigents could be manoeuvred into a position where Elizabeth could remove them that the supremacy legislation could be passed. Kitchin was either sufficiently flexible, sufficiently conscienceless or sufficiently wily not to be manoeuvred, but he was eventually outnumbered. Characteristically, faced with a situation in which he could only lose, he backed down rather than fight and be defeated. Jennifer Loach has even suggested that the initial episcopal opposition to the Supremacy was counterproductive, and forced Elizabeth into dependence on more radical churchmen in order to secure her title to the throne. It would be the ultimate irony if Kitchin, who has for so long been vilified as a spineless turncoat, should now be criticised for his intransigence.

Kitchin’s willingness to compromise could thus be justified on the grounds of realpolitik. Grand gestures of defiance are all very well, but there are times when it is ultimately more fruitful to give in and live to fight another day. Kitchin also seems to have had an awareness of his pastoral duties, and of the need to preserve some sort of continuity of care in his adopted diocese. This pastoral approach is seen most clearly in his dealings with the only Marian martyr in the diocese, Rawlins White.

According to Fox’s Acts and Monuments, Rawlins White was a simple illiterate Cardiff fisherman who sent his son to school so that he could read the Bible to his father. The two studied together and the older man became a preacher and a convinced Reformer. He was arrested on Mary’s accession and burned as a heretic in 1555. There is a touching story that on the day before his execution he asked his wife to send him his wedding shirt – his best shirt, in which he would have been buried – so that he could go to his death as to another wedding.

However, if we read between the lines of this story we can see that White was no simple fisherman but but the leader of a group of extreme radicals. He was arrested in 1554, when only the most notorious Protestants were being attacked, and a long time was taken over his case. Part of the delay, though, was due to Kitchin’s extreme reluctance to proceed with the rigours of the law. He attempted to reason with White, to pray with him, and to persuade him to accept a form of words which would save him from punishment. All else having failed, he kept him under such open confinement that escape would have been easy. White was the leader of a group of Cardiff protestants, many of whom visited him in prison, but none of his associates was proceeded against. It seems that only White’s own determination brought him to the stake in spite of all Kitchin’s efforts.

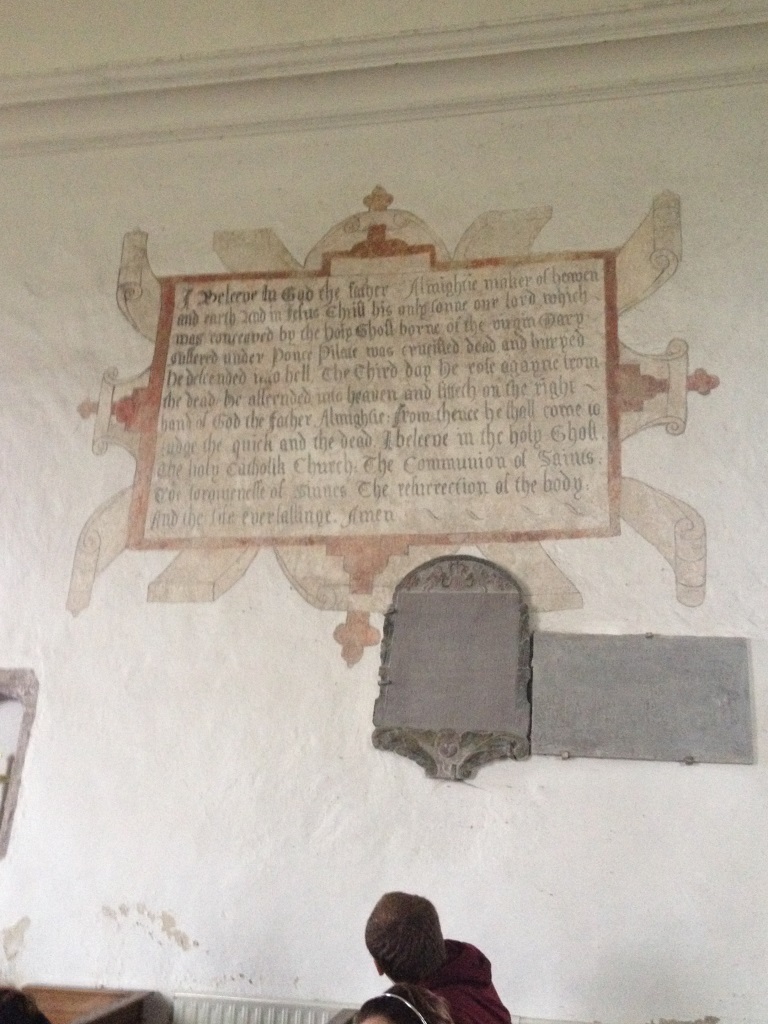

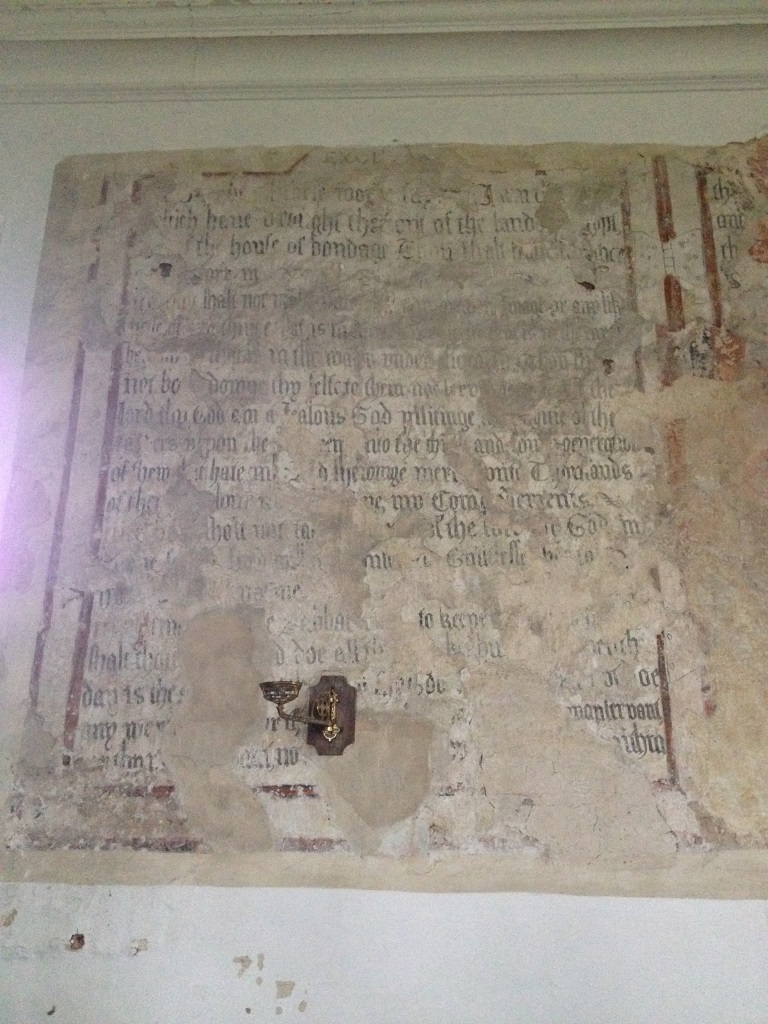

Kitchin himself was always prepared to accept the face-saving compromise and the adroit verbal formulation. His refusal to take the oath of supremacy nearly cost him his diocese in 1559, but he eventually accepted a curiously-worded submission in which he promised, without details, ‘to set forth … and cause others to accept … the whole course of religion now approved in the state of her Grace’s realm’. Opinion is divided as to whether this was in effect an acceptance of the supremacy, but Kitchin apparently felt he had made his point. He was also allowed to refuse Elizabeth’s mandate to consecrate Matthew Parker as archbishop of Canterbury, a refusal which has subsequently called into question the validity of all Anglican orders. J.C. Whitebrook’s theory that Kitchin did in fact consecrate Parker in a private ceremony is intriguing but at best unprovable. It would certainly be in line with Kitchin’s other actions to refuse publicly but to act privately to ensure the continuity of a validly ordained ministry.

The extent of Kitchin’s success as a pastoral bishop, and the justification for his sacrifice of principle, is seen in the condition of his diocese at the time of his death. Llandaff was perhaps the poorest of the Welsh dioceses: the diocesan income was a little higher than Bangor’s, but individual parishes were generally poorer. And where Bangor was in a way insulated from the worst consequences of its poverty by the fact that North Wales society was generally poor, the diocese of Llandaff was in the wealthiest area of Wales, so the church suffered by contrast. The diocese was thus hit disproportionately hard by the crisis in clerical recruitment in the 1540s and 1550s, with few ex-religious and chantry priests to fill the resulting vacancies. The survey of the clergy in the winter of 1560-61 showed many gaps in the parochial ministry, caused partly by the slump in clerical recruitment and the devastating effects of the influenza epidemics of the late 1550s and partly by absenteeism. Some of the absentees were pluralists, some were studying at Oxford or Cambridge, but some at least had left their parishes because they could not accept the Elizabethan settlement. By 1563, however, the situation had improved considerably. Few parishes were without incumbents, though there was still much pluralism; several absentees had been persuaded to return; and there had been a marked upturn in recruitment. This basic resilience must owe something to Kitchin’s pastoral skills and ability to negotiate and persuade.

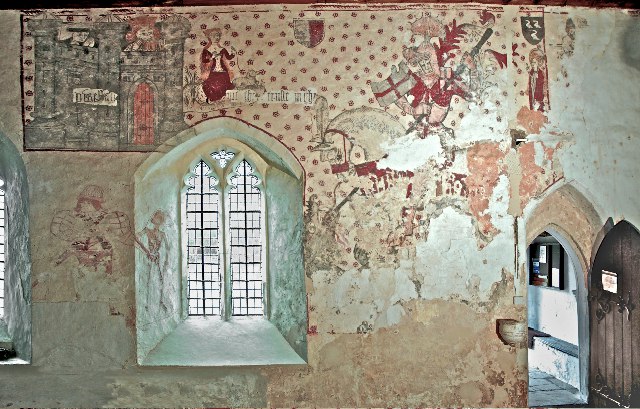

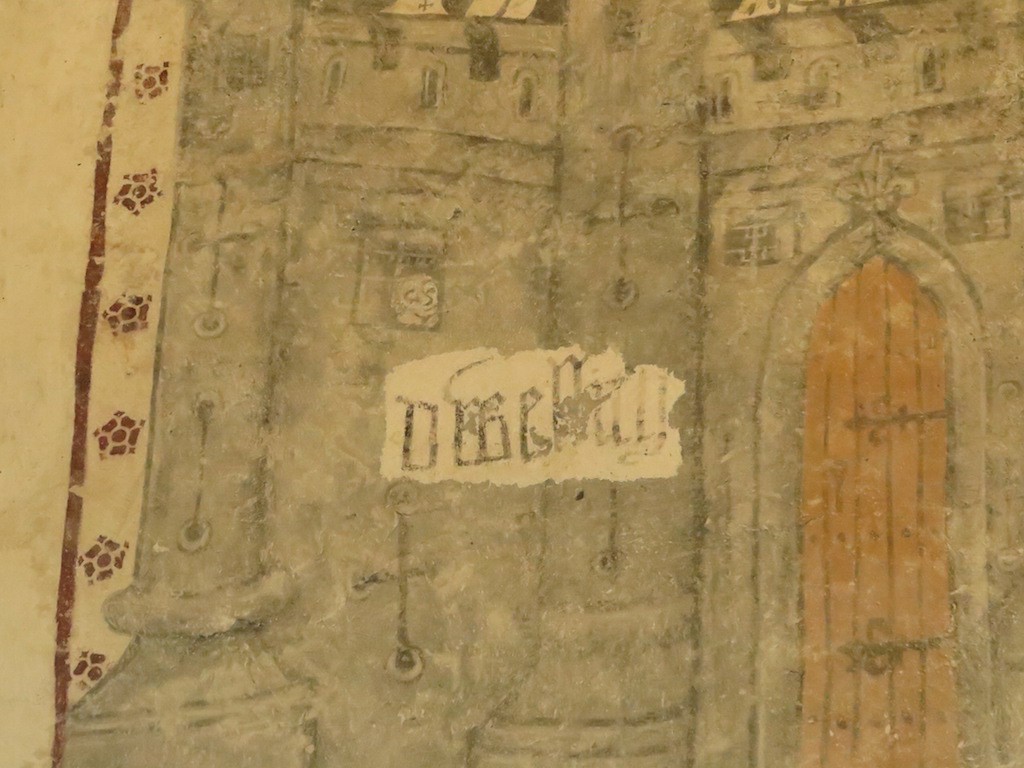

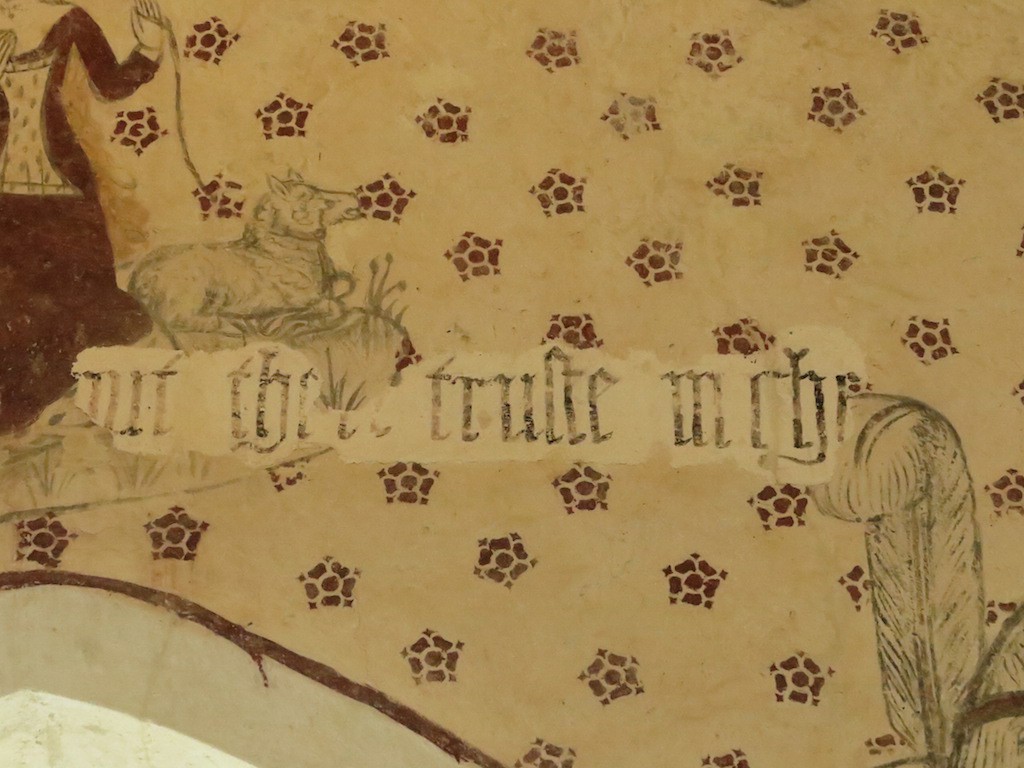

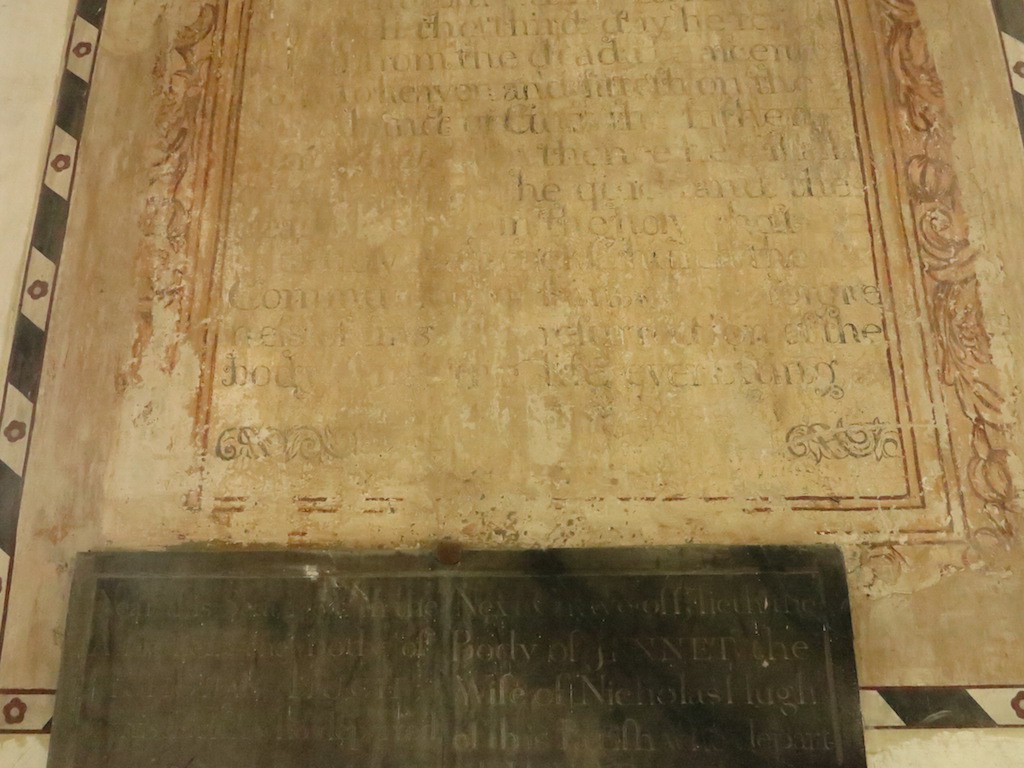

Kitchin died in October of 1563. He had been too old and ill to attend the parliament of 1562; oddly enough, one of the men who he asked to vote on his behalf was Edmund Grindal, the Puritan bishop of London. We have a survey of the contents of Mathern Palace made on Kitchin’s death because he died in debt to the Crown. He was responsible for collecting the taxes which the clergy of his dioces owed to the Crown and he had simply not done so. Laziness – or a recognition that the clergy for the most part simply could not afford to pay? Kitchin knew by then that he was dying; he had no dependents and precious little for the Crown to distrain on. It may have been his final act of quiet defiance. His possessions make pathetic reading. Old clothes, shabby furniture, a little silver plate, a well-equipped kitchen with huge cauldrons and roasting trays and the little dish in which his eggs were cooked. It all looks very much as though he had gone to the 1538 equivalent of a clerical outfitters and ordered one of everything, and had not done much shopping since. He may have been blind by the time of his death, but he still had forty books in his library: unfortunately, the surveyors did not think to list the titles. He also had some old vestments which he must have rescued from Eynsham at its dissolution.

The final argument in favour of his willingness to compromise lies in the events after his death. Nearly three years passed before a replacement was appointed. This was not Elizabethan parsimony: the diocese was so poor as to be hardly worth the effort of exploitation. Rather it was that no suitably-qualified candidate could be found to take the post. Parker himself admitted that the see was ‘so impoverished .. that few who were honest and capable could be persuaded to meddle with it’. Edmund Grindal once suggested that it should be given to his old friend and mentor Miles Coverdale, the Biblical translator. It is intriguing to speculate what sort of bishop Coverdale would have made: he is certainly the most famous bishop we never had. With his linguistic skills, he would have had no difficulty in coming to terms with the Welsh language; he might even have initiated a translation of the whole Bible before William Morgan’s, and the whole grammar of literary Welsh might in consequence have leaned more on south-eastern than northern forms. Coverdale had been bishop of Exeter under Edward, but his ideas had become more radical in exile during Mary’s reign and he was not prepared to return to his diocese on Elizabeth’s accession. Although virtually destitute, he had refused several other posts, and it was with some difficulty that Grindal persuaded him the following year to take the parish of St Magnus Martyr in London. It was therefore unlikely that, even if he had been offered the diocese of Llandaff (as the Tercentenary Tracts suggest he was), he would have accepted it.

The diocese was eventually given to Hugh Jones, the rector of Tredynog in the Usk valley. It may have been an appointment born of desperation, but the new bishop was at least a local man, a preacher, and the first bishop for over three hundred years who could actually speak the language of the majority of his people. He had long been one of the senior clergy of the diocese and may have functioned as Kitchin’s unofficial deputy: he was certainly prepared to follow his policies of conciliation and compromise.

One of the great unanswered questions of the Reformation in Wales is why the people of Wales, against all the odds, failed to rebel against religious change. All the evidence suggests that the Welsh were happy with traditional Catholic piety and saw no need for reform. But faced with the destruction of shrines and monasteries and a prayer book in an alien language, they made no open protest. The consequences of such a rebellion would probably have been disastrous, in a country which was only now recovering from its last struggle for independence. By the time Jones died in 1574, the New Testament and the Book of Common Prayer were available in Welsh; fourteen years later, with the publication of the whole Bible, public opinion in Wales as articulated by the popular poets swung squarely behind the Elizabethan settlement. In spite of the localised and increasingly marginal Catholic resistance, the Reformation was well on the way to being secured: and it is at least arguable that it was the tolerance of men like Kitchin and Jones, rather than the confrontational policies of men like Jones’s more famous successor William Bleddyn, which helped to secure peace, religious stability and the future of the Anglican church in Wales.

For the inventory of Mathern’s contents on his death, click on this link: Mathern Palace in 1563

[i] see, e.g., J.A. Scarisbrick, The Reformation and the English People (Oxford, 1984) esp chs 4-7