Sometimes it’s the things that everyone knows that turn out to be the most puzzling – and also the most illuminating. A couple of years ago we had an interesting discussion on the medieval-religion Jiscmail list (http://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/medieval-religion) about the Croes Naid, the fragment of the True Cross which was the most valued part of the regalia of the Welsh kings of Gwynedd. The name has been variously translated as the Cross of Destiny or the Cross of Refuge (by the Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru, Wales’s equivalent of the OED: see http://anglonormandictionary.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/word-of-month-croes-naid.html and http://www.welsh-dictionary.ac.uk/ ). Seized by Edward I after his defeat of Llywelyn and Dafydd ap Gruffydd, it ended up in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where a carved boss still depicts its reliquary. But its journey there was anything but simple.

For Christmas my lovely husband gave me a book on the graveyards of the City of London (how well he knows me). I want to visit them all. We made a start on a recent visit by taking a line from Bunhill Fields to St Olave Hart Street. On the way we passed St Helen’s Bishopsgate: nice little graveyard, now a garden between high office blocks and in the shadow of the Gherkin.

People were coming out of the lunch-time Bible study – men in expensive tailoring, students in jeans, lots and lots of people. In we went. The church was still full and buzzing, people eating sandwiches, other tourists wandering around, a couple of meetings in the transept. Eventually a welcomer came up to us, answered a few questions and lent us a copy of the church guide book. (Yes, we did go and buy a copy of our own.) The welcoming strategy was Good – let people look around first, approach them with a welcome, ask a few open-ended questions, decide they were academics, offer some literature, let them get on with it. Then she discovered we were Welsh and introduced us to the minister. He is Welsh. He speaks Welsh. We still get everywhere.

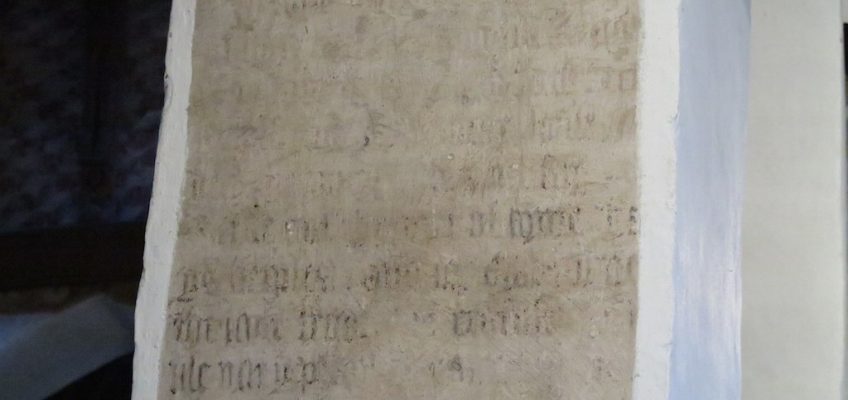

St Helen’s (formerly the nunnery of St Helen) is one of the City of London’s few surviving medieval churches, with a stunning collection of medieval and post-medieval tombs and a remarkable claim in the guide book. We were told that in 1285 Edward I gave the church a cross called Neit which he had ‘found’ in Wales. So if the Croes Naid was in Bishopsgate, what was in Windsor?

Back home, I sent a hopeful email enquiry to the church. I was worried that relics and relic cults could be tricky for evangelical Anglicans but the current and previous building managers got back to me with encouraging speed. The guide book was based on the Survey of London volume – which referenced Edward I’s wardrobe accounts and the Rolls Series edition of his chronicles – then I found my notes from the earlier discussion on medieval-religion with some online articles and a few more references to edited texts. Back to the literature. I’m still happiest if I have some paperwork.

We still don’t know where the Croes was before it was surrendered to Edward I. In Celtic Britain and the Pilgrim Movement (p 100) Griffith Hartwell Jones says it was on Llywelyn’s body when he was killed, but he gives no source for this and the sources he quotes for the hand-over of the Croes don’t say where it was found. Personal reliquaries were common, and it is quite possible that Llywelyn would have wanted this precious relic as near to him as possible: but if he was killed by an English raiding party (and his body was subsequently mutilated and his head taken and placed on Traitor’s Gate in London) how did the relic remain in Welsh hands to be surrendered the following year? Other traditions suggest it was kept by the Cistercian monks of Aberconwy. It was certainly at Conwy that it was handed over to Edward. The Aberconwy community had been moved from Rhedynog-felen, near Clynnog, by Llywelyn’s grandfather Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, who wanted them nearer to his palace at Deganwy. Llywelyn ab Iorwerth himself took the monastic habit at Aberconwy shortly before his death and was buried there.

The Welsh Rolls of Edward I describe the Croes being handed over at Conwy by ‘Einion son of Ynor, Llywelyn, Dafydd, Meilyr, Gronw, Deio and Tegnared’: as a reward they were released from any other royal service. (Rot. Wal. 2 Edw. 1 m. 1; Rymer, Foedera, i, 63). On the other hand … according to the chronicle of William Rishanger, a monk of St Albans (online at https://archive.org/stream/willelmirishange00rish#page/104/mode/2up ), it was Dafydd ap Gruffydd’s secretary who brought the relic to Edward. This was presumably the Hugh ab Ithel who was given a scholarship at Oxford as a reward (Hartwell Jones found this in the royal wardrobe accounts for 1284). The royal warrant recording its surrender stated that the relic had been passed from prince to prince down to the time of Dafydd ap Gruffydd. It looks rather as though the relic had been in safe keeping somewhere, but not necessarily at Conwy, which was in Edward’s hands by the end of 1282. The rulers of Gwynedd had close links with the abbey of Cymmer and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was buried at Cwm-hir. Both are possible candidates.

Dafydd was still alive when the Croes was handed over. In September he suffered the horrific death of a traitor, being hanged, drawn and quartered, the four parts of his body sent to the four quarters of the kingdom and his head placed on the Tower of London. All this rather puts paid to Edward’s claim to have ‘found’ the relic in Wales. This was more than a simple surrender: it was forcible translation of the relic, on a par with Edward’s ‘acquisition’ of the Stone of Scone a few years later.

Edward took the Croes to London in the spring of 1285 and carried it in a great procession to Westminster Abbey on 30 April (Flores Historiarum iii, 63). A few days later, on 4 May, with another great procession, he took it to St Helen’s Bishopsgate and presented it to the community of nuns there (Chronicles of the Reigns of Edw. I and Edw. II (Rolls Series) i pp 93-4). We have no idea why the nuns were the recipients of this stunning piece of royal generosity: it may have seemed appropriate, as the community was dedicated to St Helen, mother of Constantine and finder of the Cross. The first mention of St Helen in connection with the Croes Naid was not until 1354, when Edward III petitioned the Pope for a relaxation of penance for those visiting St George’s Chapel. In the petition he said that the chapel contained a cross brought by St Helen and destined for England. It is possible that this reflects an earlier tradition linking the Croes with Helen: she appears in Welsh legends, including the Dream of Macsen Wledig in the Mabinogion. In his Historia Regum Britanniae Geoffrey of Monmouth had included the story that Helen brought a fragment of the True Cross to Britain, but did not identify it as the Croes Naid.

But Edward’s generosity was a fragile thing, and the Croes did not stay in Bishopsgate. The priory was still being described as thepriory of Holy Cross and St. Helen in 1299 (http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol9/pt1/pp1-18#fnn33 ), but by 1296 Edward had reclaimed the relic. That year, he took it on his Scottish campaign, and it was on the Croes that Wishart, bishop of Glasgow, was forced to swear fealty to the king. Edward may initially have intended to ‘borrow’ the Croes, but once it was back in his custody he hung on to it. We can trace its movements round southern and eastern England in the royal wardrobe accounts for 1300 (online at http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=C4QPAAAAIAAJ&pg=PR1&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false ): at Windsor on 2 Feb (p. 28), at Stratford Langthorne Abbey on 3 April (p. 32), at the Dominican friary at Stamford (Lincs) on 3 May (p. 35) and in the chapel of Wisbech Castle (Cambs) on 19 May (p. 36). On each of these occasions Edward offered money to the Croes and to a thorn from the Crown of Thorns. Was this another relic which had been surrendered to him in Wales, or had he acquired it elsewhere? The Croes went north to the Scottish borders in the autumn of 1300: in September it was at the abbey of Holm Cultram, near the Solway Firth. Edward took it to Scotland again on his final campaign in 1307. After his death it was kept in the Tower of London until Edward III gave it to Windsor.

It is just possible that the Croes was returned to Wales for a while. A story in the collection of miracles of St Thomas Cantilupe describes an incident in Conwy in 1303. (Susan Ridyard and Jeremy Ashbee have just finished a study of the story as part of a larger work on the miracles of St Thomas Cantilupe. Susan Ridyard has kindly sent me the final draft of this fascinating study, with all its circumstantial detail of everyday life and social tension in what was still a garrison town.) A small child fell into the castle ditch and was thought to be dead. According to some of the subsequent depositions a burgess of the town vowed to St Thomas that if the child recovered he would go on pilgrimage to St Thomas’s tomb in Hereford. Immediately the boy recovered. But an alternative version of the same story credited his recovery to the Holy Cross of the church of Conwy ‘for which God very often works miracles in the town’. The Holy Cross of Conwy may have been one of Wales’s many miracle-working rood carvings, though it is surprising that no poetry mentioning it survives. Alternatively, it could be a memory of the Croes Naid, recalling either its time at Aberconwy Abbey or its return to Wales on one of Edward’s visits. The last of those visits, though, was in the spring of 1295 (according to the List & Index Society’s Itinerary of Edward I). By 1303 the Croes was back in England. It is still possible, though, that what Conwy had was a contact relic, possibly something that had housed the Croes and still retained some of its power.

The Scots have managed to get the Stone of Scone back but the Croes Naid was almost certainly destroyed during the reign of Edward VI. Does it matter? Should the Welsh still feel sore that a scrap of wood was taken from Conwy when we lost so much else as well? Supposing it turned up at Windsor … or supposing we found the famous statue of the Virgin Mary, hidden at Penrhys … or the bones of St David … what would it mean to us now?