Another lovely afternoon, this time at the National History Museum in St Fagan’s watching the conservators paint the texts under the re-created wall paintings. Their experience must be something like that of the original painters: they are painting texts mainly in Latin, in black-letter script. It’s not so much writing as paintings of words. There are decisions to be made about abbreviation marks, and occasional mistakes. The dynamic must be very similar to that in a medieval parish when texts had to be chosen and written out, then painted and (presumably) checked by the priest.

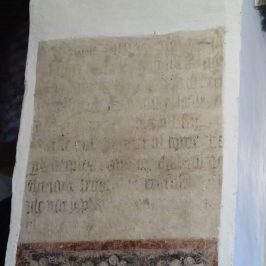

This whole business of text in wall paintings is very odd. We were surprised by the amount of writing we found on the walls of St Teilo’s. There were captions – ‘Ecce Homo’ above the Bound Christ, ‘Sancta Trinitas’ under the Trinity – but perhaps more significant was a series of prayers which could guide worshippers round the church. The Image of Pity had what looks like the famous late medieval prayer ‘Jesu mercy, Lady help’ (interesting that this one was in English) and a fragment of a litany, ‘A dent …’, possibly ‘A dentibus mortis’ or ‘A dentibus infernis’ … from the teeth of death, good Lord deliver us. Under the north-west window was something we have interpreted as ‘Jesu Christe deus et homo da nobis pacem’ – ‘Jesus Christ, God and man, give us peace’. This sequence has now been fleshed out with quotations from familiar Bible passages and bits of the Easter services to accompany the paintings which tell the story of the Crucifixion.

But why would a medieval congregation have spent time and money on painting texts on its church walls when hardly any of them could read? Of course, even if you couldn’t read, writing was Important – it told you that what you were looking at was significant. It could even have magic powers. Badges with fake writing on them, charms in strange garbled words on scraps of paper – these all suggest writing had power.

But there is more to it than that. Some of the writing was probably recognizable, even if you couldn’t read it all. The A and M of Ave Maria, the J of Jesu Mercy: people learned to identify these and to respond to them. And the efforts they went to suggest that writing had meaning for them, even if they couldn’t ‘read’ it as we would use the word. They knew it could be read, it could be read to them, they could learn what it meant. We identify the pictures by their captions; they recognized the text from the pictures.

Of course, all this is a huge challenge for the Museum to explain. Few of their visitors will be familiar with the Latin liturgy, or even with the Bible stories on the walls. They do not want to over-interpret: it’s important that visitors experience the building for themselves. But how do you explain a medieval church to a modern audience?

Why are they pouring water on that man’s head?

Why are those men kissing?

Why is that lady showing her breasts?

3 Responses